Last week several White Oak staff received two emails at their work email addresses, purportedly from a high-ranking officer at our company. The emails were asking us to give them our personal cell phone number as soon as possible, as the officer in question had an urgent task. Most of you reading this have likely gotten similar emails in the past; if not, check your spam folder as you probably just haven’t noticed them.

Phishing Email

I had received these emails at previous employers also, typically along with many other colleagues. At one previous employer we determined that, based on the timing of the emails received by different employees, it was likely triggered by a change in job status on LinkedIn. The individuals receiving the emails had all recently been hired at the company and had only days before changed their associated company in their LinkedIn profile.

This indicates that the spam senders may have some automated scraping script to check LinkedIn for newly changed profiles or by looking at particular organizations and periodically doing a “diff” on the employee lists to find new additions. The approach used in this phishing campaign would also require research into authority figures in the company to use as the sender of the emails. This is probably automated through the API as well.

In this most recent instance, several employees at the company had received similar emails, regardless of their length of tenure, so it’s possible the scammers skipped the first step above and just picked recipients at random.

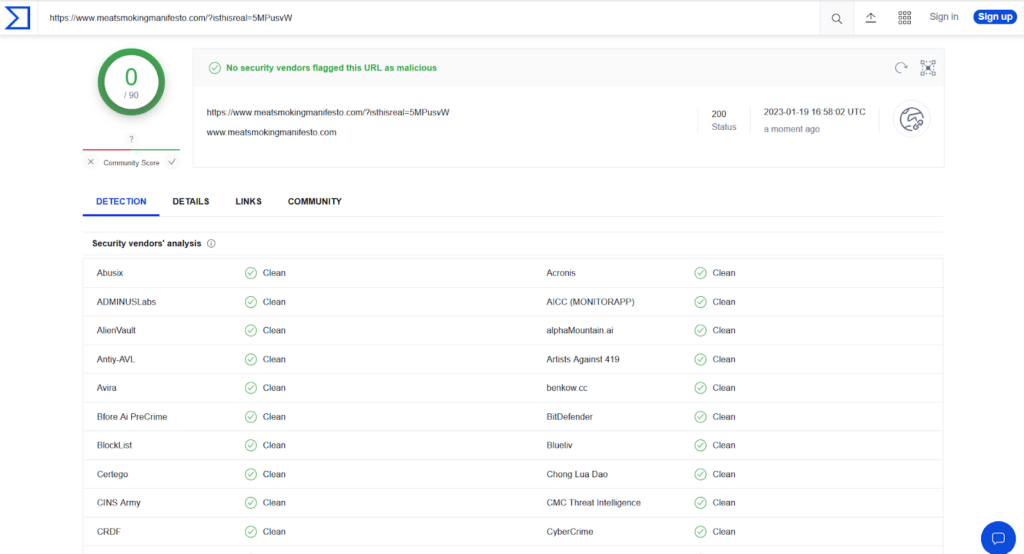

Most spam emails seem to be widely distributed and often have links or attachments included as an exploit vector. What drew our attention about these is that they avoided including any sort of immediate payload. This is presumably to help improve delivery to the target. Most spam-prevention solutions scan for malicious links or attachments and bypassing these is becoming increasingly difficult. Eliminating that potential for being flagged as spam is a clever way to get around those protections.

A second initial curiosity about these mails was that they specifically asked for a phone number. We weren’t sure what the endgame was for the senders: are they trying to do some sort of sim-swapping scam? Maybe something involving multi-factor authentication?

The emails are simple and they evoke a sense of urgency by pretending that the new employee’s boss or some authority figure needs their immediate help. This increases the employee’s likelihood of compliance, as they’re afraid to question the request to avoid potentially upsetting the boss. The urgency requires them to act quickly and not think as critically about the request. For readers interested in the psychology of these methods of persuasion and why this works so well for scamming, we’ll refer you to Chris Hadnagy’s excellent book “Social Engineering: The Science of Human Hacking”, specifically chapter 6 “Under The Influence”.

The first email received had the display name of the email set to an officer of the company, but with an actual email address of t[REDACTED]@cox.net.

Here is an example of the initial email received, supposedly from <BOSS REDACTED>:

—–

Hi

Could you re-send me your cell #, I need you to get something done ASAP and wait for my text.

Thanks

—–

We reviewed the spam mailbox and noticed that it received two such emails within the same week from two separate emails: one a Gmail account and one from the cox.net email account.

After gaining approval to reply (from our actual boss), we wrote back to both emails and asked what they wanted, without giving a phone number.

—–

Hi <BOSS REDACTED>,

What can I do for you? Is it something urgent?

Thanks!

-J

—–

Only one of the two accounts responded, the one from cox.net. If it is the same group, that indicates that they may be rotating through email addresses and only responding within a specific time window. The one that did not respond was sent earlier in the previous week.

Phishing Scam

The sender answered with the exact same message as they had originally sent, so we weren’t sure if the entire process was automated or whether it was an actual human on the other end of the communication.

One interesting detail to note: in the response, the sender had forgotten to modify the display name on the email so there was another person’s name instead of <BOSS REDACTED>. Also interesting, that name did not correspond with the original name of the user based on the email account name structure at cox.net. That indicated to us that they were getting their phishing campaigns mixed up and the process likely wasn’t scripted.

We responded with the following text:

—–

Hi <BOSS REDACTED>,

I don’t have a cell phone, sorry. What can I do for you? Feel free to drop me a quick email, I’m happy to take care of whatever you need.

Thanks!

—–

I wanted to see whether the emails were being automated and what they would do if we didn’t give a cell number. Surprisingly, we received a very human response in just a few minutes:

—–

I want you to locate any store close by, i need you to get me some cards. I need those cards for a presentation in a few. How soon can you get this done?

I want two ITunes cards, and i want each card in the denomination of $200 Ok

—–

*Eye Roll*

So, rather than being something complicated and sinister, it seems the goal of these scams is the same as the typical “iTunes gift card” scams seen on most “scambaiting”-themed YouTube channels. This group seems to have just taken it a step further to try and bypass typical spam filters by convincing the victim to use text messaging rather than email. To facilitate this sort of scam, there’s no real need for a complicated C2 infrastructure or web hosting per se, just the ability to send emails from a compromised account and some time to kill. Additional reasons to use texting instead of email are to make the sources harder to trace and to get a phone number to facilitate later phone scams.

We replied to the email as if we were going along with the scam:

—–

Hi <BOSS REDACTED>,

Sure, no problem, can I just expense those on the corporate card? Do they need to have names on them or is just regular cards ok?

—–

The sender then replied:

—–

I will reimburse you immediately am done with my presentation okay

—–

Judging by the grammar mistakes and word ordering, the sender is probably not a native English speaker and thus most likely not in the United States. This is not surprising and is common for phishing/spam email campaign creators.

This foray into the world of scams wasn’t intended to be any sort of real legal or forensics investigation, more just a passing curiosity of what the scammers goal really is behind sending these particular sorts of phishing emails.

Phishing Attack

While we weren’t interested in doing anything illegal to further the investigation, we did want to know a little more about these people and where they were from. We decided to use an email tracking pixel in the next email to see if we could determine where they were accessing the compromised email accounts from.

For those who aren’t familiar with them, email tracking pixels are small HTML image tags embedded in emails with HTML content. They’re often used for marketing purposes as “read receipts” to identify whether a targeted user has actually opened a marketing email. They are used similarly for collecting metrics for internal phishing campaigns on which users opened phishing emails. In this case, we wanted to see if we could get an IP address from which the senders were viewing the emails.

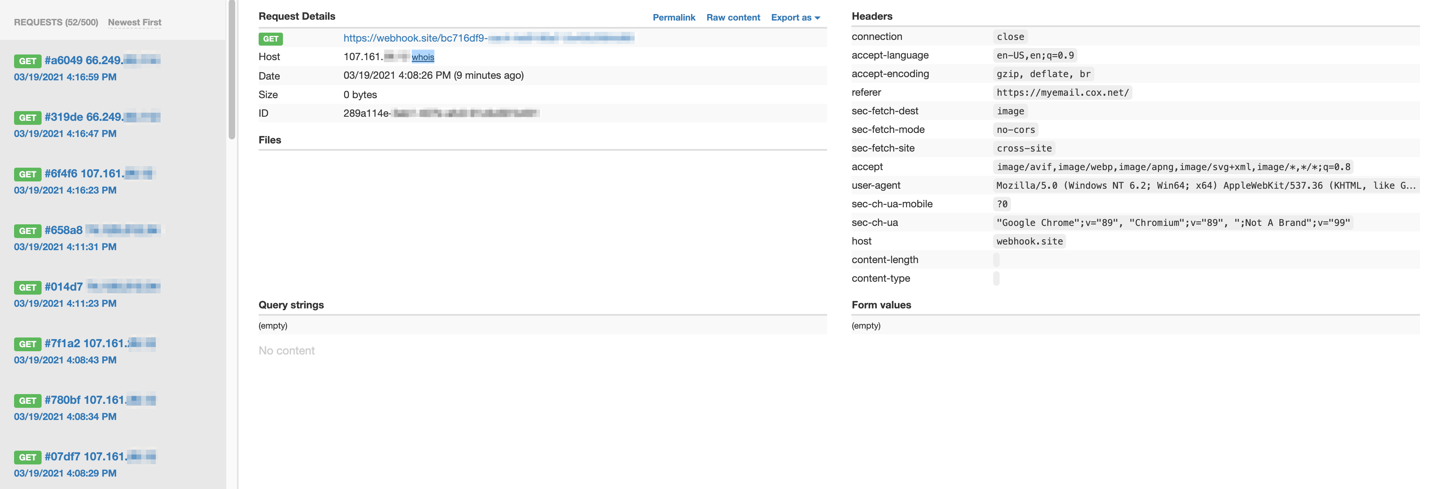

To create the tracking pixel, there wasn’t a need for a complicated setup. We used a free site called https://webhook.site which is normally used for testing API webhooks. It provides developers with an anonymous URL to run GET and POST commands against in order to test their web application calls. The status page gives basic information about web requests made to the anonymous URL such as the user agent, the referrer URL and the IP address making the request.

The tracking pixel used this format:

—–

<img src=”https://webhook.site/<GUID VALUE FOR ENDPOINT>” width=”1″ height=”1″>

—–

In the meantime, we apparently had been taking too long to respond and received this email:

—–

I have just 10 minutes left to complete my presentation how soon can you help me get this done

—–

The scammers were turning up the pressure and apparently getting impatient. We inserted the tracking pixel into the HTML content of the reply and responded with:

—–

Hey, sorry I got sidetracked, what should I do with them once I get them?

—–

Then it was a matter of waiting. In the webhook.site details page for the endpoint, we could see several accesses by Google URLs, apparently checking the image link for malicious content, but not directly requesting the endpoint as an image. These were obviously benign after looking at the WHOIS data for the IP addresses.

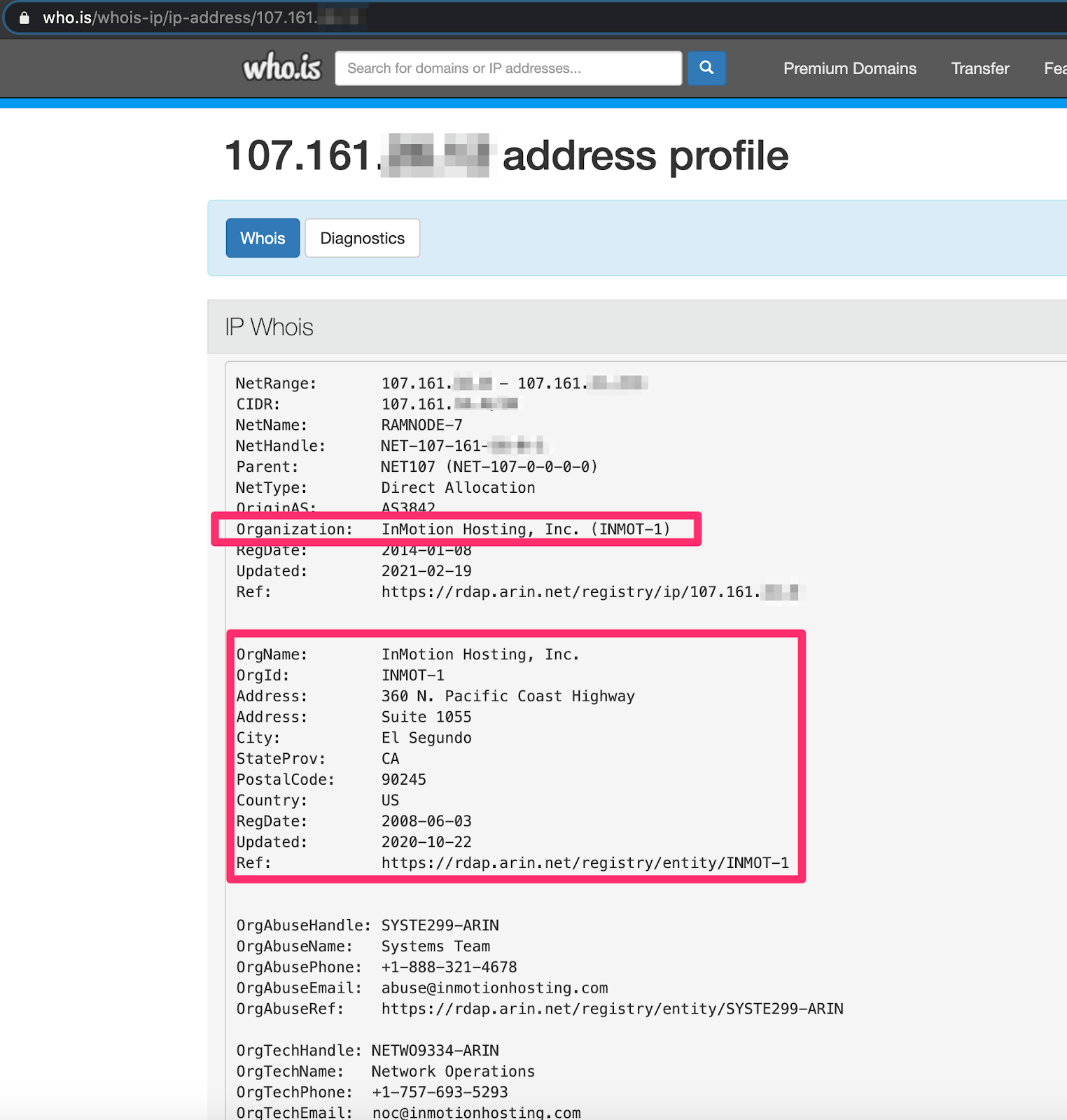

Then after just a few minutes, there was a more surprising hit: a 107.161.X.X address, attempting to request an image at our endpoint with a referrer URL of mymail.cox.net. This was interesting to us for a few reasons. The first was that it seemed that perhaps the senders were actually accessing the mymail.cox.net web application directly, logged in as the compromised user and not just emailing through a backend web client or something scripted.

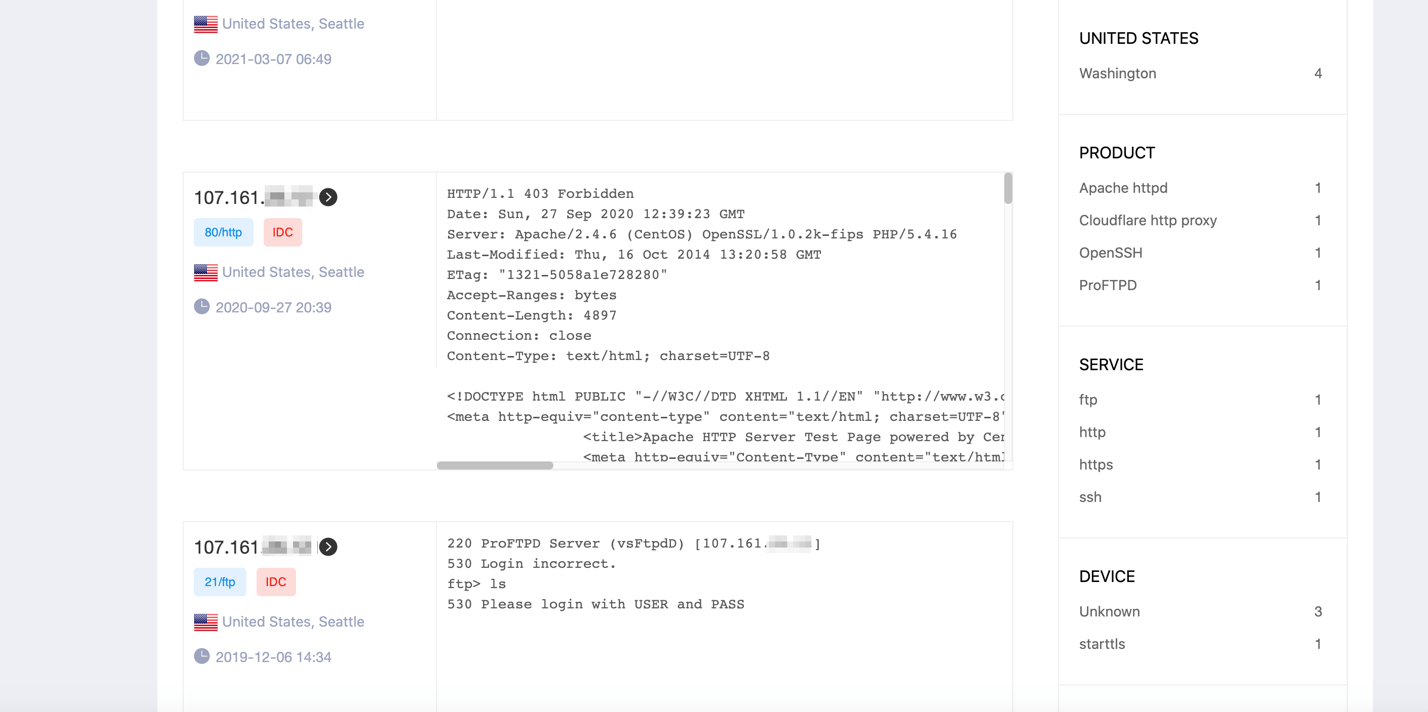

The second interesting feature was the IP address. According to WHOIS, the IP was part of a block of addresses allocated to a company called InMotion Hosting, a website hosting and Virtual Private Server hosting company. Our guess is that the senders were proxying through a VPS in order to access the mymail.cox.net website to send and receive emails.

During our analysis, we received a response:

—–

Once the cards are purchased at the store, scratch the silver panel at the back of each card, and take a photo revealing the back codes and send me the images and receipt image too

—–

At this point there was enough information to determine what was going on and there wasn’t a need to continue. After about an hour though, we did receive one final email from them:

—–

Are you there <White Oak Employee> ? have you gotten the cards ?

—–

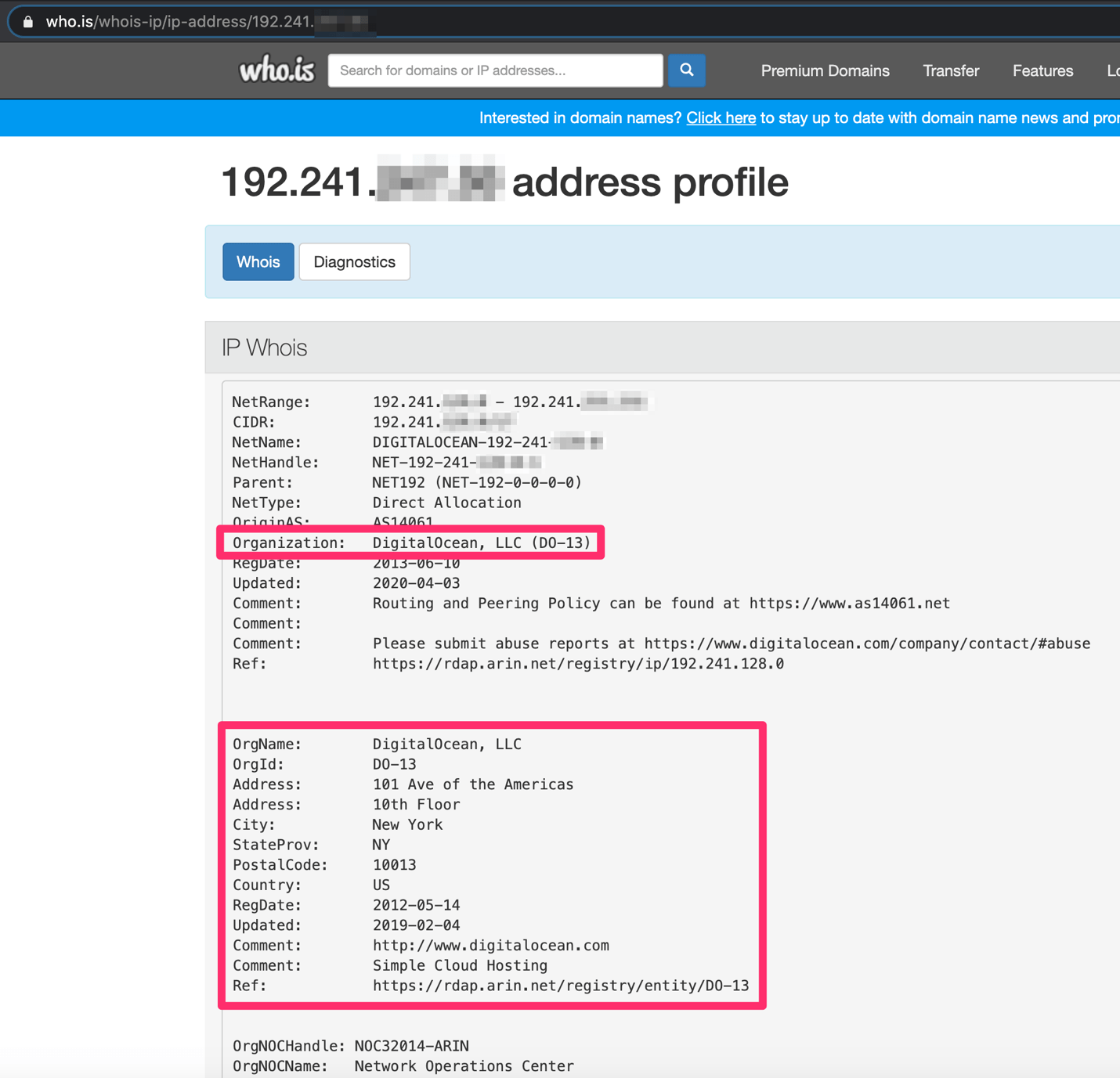

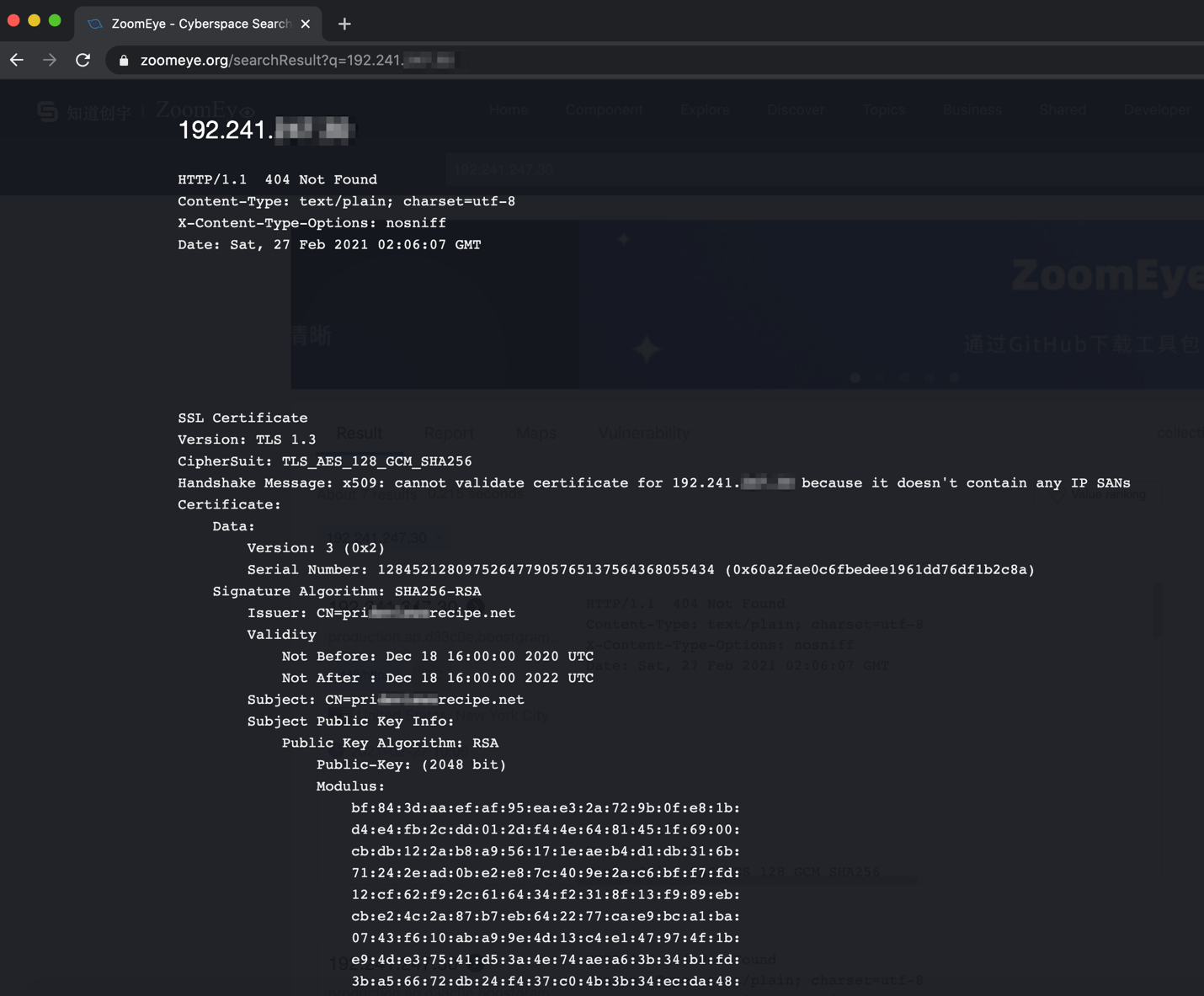

Interestingly, during the interim period, the pixel tracker did receive several other separate hits from a different address: 192.241.X.X. According to WHOIS, this IP block is allocated to DigitalOcean, another VPS hosting company. These were also making a direct request for the image and also referred to from mymail.cox.net. The assumption is that after we stopped responding, the original sender was asking someone else to look at the email or they had taken over duties for them.

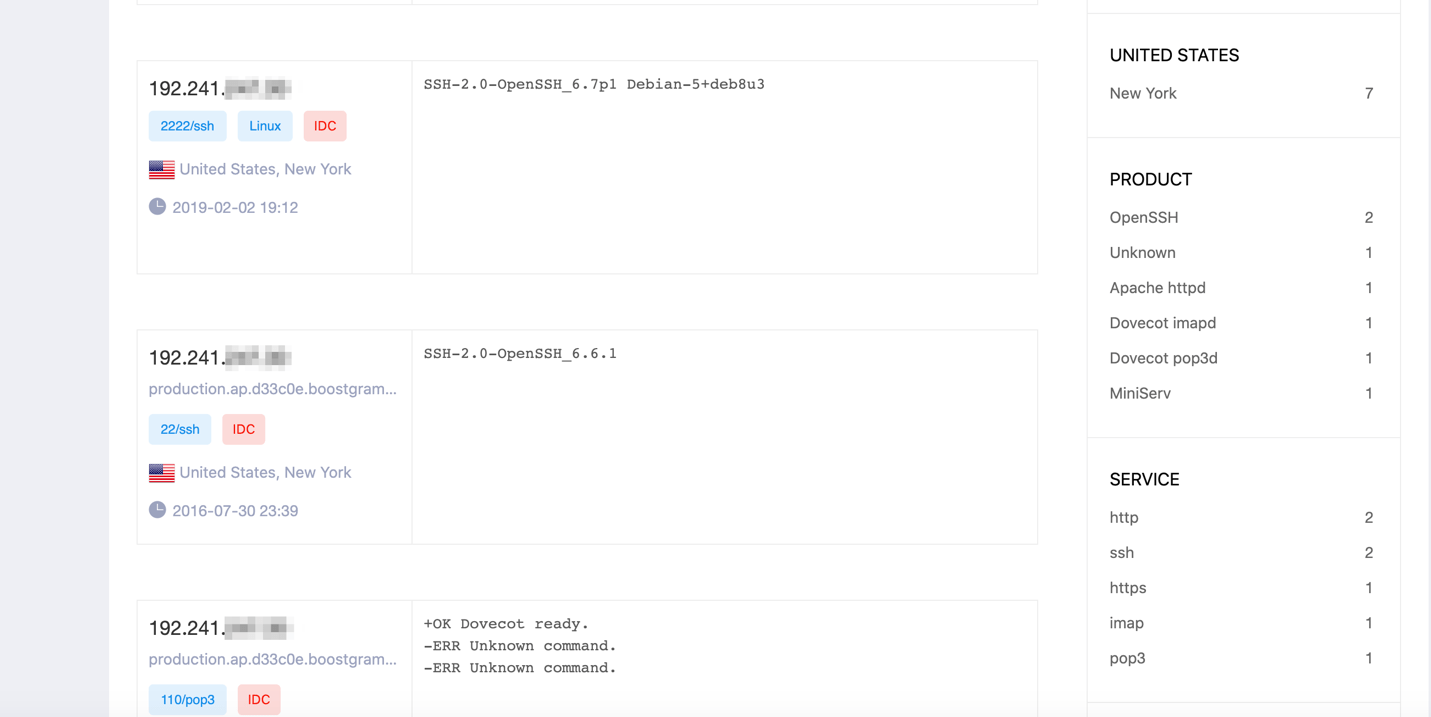

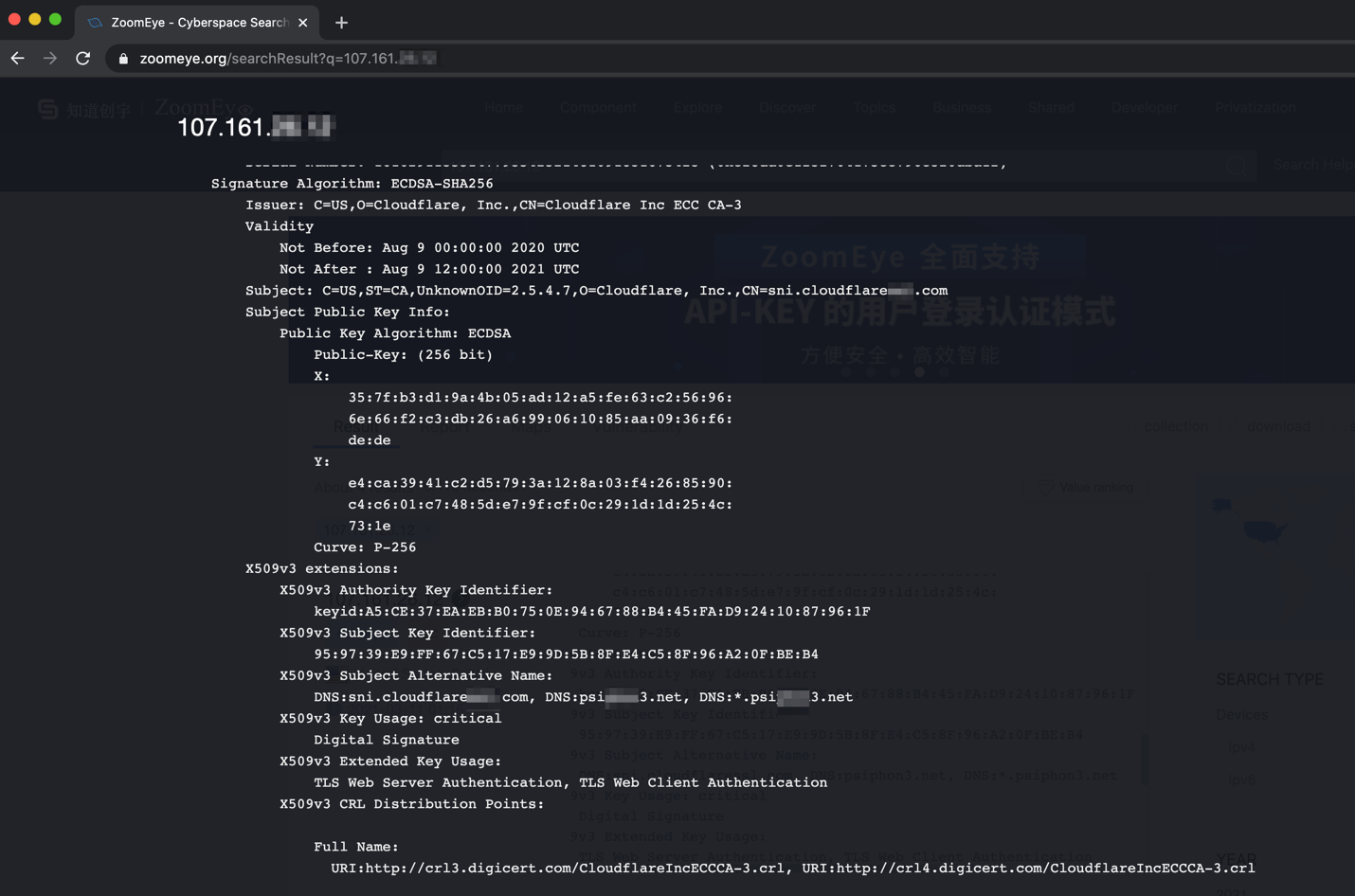

Taking a look at the IP addresses in question using a free alternative to Shodan.io, it appears these VPS servers are potentially being used long term. One has what appears to have two separate sketchy sounding domain names associated with its webserver. It also appears to have an email server set up, presumably for sending outgoing phishing/spam emails.

The second IP has a webserver also with potentially suspicious domain names associated with the SSL certificate and has an FTP server running. Both servers have SSH access enabled externally.

A Modest Investigation

Because the investigation was not, and was never meant to be, rigorous we didn’t report the VPS IPs to their respective hosting services. Aside from that, some VPS services make it difficult to report such things and without concrete assurance of any wrongdoing, it doesn’t make sense to file complaints. A more diligent investigation may uncover stronger evidence, however.

While this modest investigation doesn’t really hold any legal or forensic value, it was still an interesting look into the email scams we get on a daily basis and gave some insight behind the scenes. It illustrated that although the phishing emails may seem targeted, in the end they are likely simple gift card scams. It was also interesting to see that the senders seemingly have some long-term infrastructure and are cautious enough to proxy through an intermediate host when checking compromised emails.